This week’s Succession is upsetting. It is upsetting because the degree of cringey discomfort was above safe levels, but also because I watched in the knowledge that the sorts of people represented therein not only exist but hold enormous sway on our collective fate. The show, as I pointed out last year, has continued to reprise themes from a rather different satire of the stupidity and vice of the moneyed class, Arrested Development. This week’s episode is an uncanny reimagining of GOB’s brief, disastrous stint as CEO of the Bluth Company, in which he reveals “Phase II” of the Bluth Company’s “Sudden Valley” Housing Development, which turns out to be just a second model home. But it isn’t even that, the Bluths want to generate excitement from the shareholders, but don’t have enough time, so the various out of work hangers-on of the Bluth Company build not even a model home, but the facade of one. But this doesn’t stop GOB, complete with “business model” Starla, from bragging the project is “Solid as a Rock”—though if you don’t pay great attention, you might hear “Solid as Iraq,” which Will Arnett’s delivery seems to encourage—a reminder of George Sr.’s “light treason” in the form of business dealings with Saddam. The corruption of the American upper class is a sort of seamless garment.

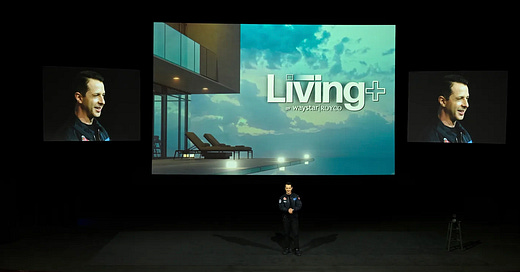

This is also the theme of Kendall Roy’s GOB-ish presentation to the Waystar-Royco shareholders, where he attempts to “hockey stick” the value of the company out acquisition range by chaotic-neutral Euro-techbro, Lucas Madsen.1 Kendall’s “new product” is an ominous sounding “land cruise” housing development called, and here I think the Succession writers came close to losing what verisimilitude remains available to them, “Living+.” Taking a page directly out of GOB’s playbook, Kendall orders his poor team to build a “practical” house with “clouds” above on the stage in less than one day. The episode theme for newly-succeeded Co-CEOs Roman and Kendall is that they are not their dad. Their despotism is feeble, desperate—chief legal officer Gerri Kellman comes close to telling Roman he doesn’t have “hiring and firing power;” Kendall bans the use of the word “no”—because they truly don’t know what they’re even doing anymore. They do not, in fact, seem to want anything. As Shiv points out, while their dad was still alive, the goal, never formally abandoned, was to sell Waystar Royco in order to buy the New York Times “Pierce Media” and compete with Logan’s ATN. What is the goal now? When pushed, Kendall says he wants to keep the company and buy Pierce—but, we know that’s not going to happen.

Clad in a custom “CEO” bomber, Kendall’s presentation includes a too-pathetic-to-be-actually-cringe “conversation” with a manipulated video projection of his dead father. The “Living+” gated communities are based around a promise of “security, entertainment,” and, incredibly, “life extension.” This is what Kendall thinks people want, and, eo ipso, what Kendall imagines is the “point” of living. Is caring only for “security, entertainment” and “life extension” the same as caring for nothing? These goals seem like pale imitations of life itself, pleasure, and, well, eternal life, and there is no pretending that such desiderata are not provided by money and thus by Waystar Royco. But each one is manifestly impossible to guarantee in the long run: there’s no way to secure security, most entertainments gets boring eventually, and you will die, maybe on the loo of your private jet. Kendall never mentions happiness in his presentation because he can’t even imagine it, although we can infer that he might consider it to be something like love—or even mere approval—from Logan Roy.

The “Living+” presentation was hard to watch, but also elicited the only thing akin to recognizable human life from most of the characters in this episode, as they cruelly mock Kendall. Thus Roman: “big shoes, big hat, big nervous breakdown.” But this very mockery shows us how completely rudderless the Roy siblings have become. In a general sense, the characters in Succession don’t actually seem to enjoy anything. They have no hobbies, no passions, they rarely go outside,2 spending their time in identical corporate non-spaces and tasteless, characterless luxury. At least the rich used to have the decency to be idle and vulgar. But the remaining Roys and their hangers-on don’t really seem to love money, they don’t even truly love dominating others, they don’t love love. Their nihilism is so unvarnished I can’t help but wonder whether, in my ninety minute exposure each weak, I’m not in danger of getting a splinter. The episodes feel like Shiv and Tom’s game of “bitey:” can I sit through all of this, or will I be the first one to admit the teeth are in danger of breaking the skin?3

In last night’s episode I noticed that even before Kendall banned the word “no” in his presence, nobody ever disagrees with anyone else, even when they want to. Sarah Snook’s brilliant performance excels here because Shiv’s dialogue is largely comprised of significant looks (which contain no actual significance) and words that border on meaninglessness: “Yeah? Yeah. Ok. Unh-hunh. Uh-hunnnhhh. Right.” She communicates without saying anything, as speech needs to express some thought or desire, and it’s not clear that Shiv, or her brothers, could articulate either of these things.4

The problem with insane amounts of money is that money, as Aristotle long ago observed, is a sign of one’s need for others. If someone has so much wealth that they don’t actually depend upon anyone else—despite being, perhaps, the most dependent on others, on the conventional life of the community that stands behind currency— then money cannot fulfill its purpose, and indeed undermines rather than facilitates a humane economy. The rich, then, imagine themselves without need. And being without need is, it goes without saying, to be without desire, let alone passion.

Money then becomes, as Kierkegaard much later observes, only an “abstraction.” The love of money is a love of abstract possibility—which is to say, of nothing. The unchecked love of money becomes nihilism “at the speed of business.” In The Present Age Kierkegaard shows this dynamic with surprising economy:

Men, then, only desire money, and money is an abstraction, a form of reflection . . . Men do not envy the gifts of others, their skill, or the love of their women; they only envy each others' money. . . . These men would die with nothing to repent of, believing that if only they had the money, they might have truly lived and truly achieved something.

The established order continues, but our reflection and passionlessness finds its satisfaction in ambiguity.

“Eat the rich” is an ugly phrase, and class warfare is the absence of politics, not its fulfillment—but…

But while Succession has become increasingly hard to watch, its moral and political intention is clear: the billionaire class if it is to persist, at the very least shouldn’t be in charge because the love of money is so abstract as to be indistinguishable from nihilism. That’s a pretty good argument for redistribution, too. But insofar as we, too, desire “Living+” we’re complicit in creating the world where they call the shots—and refusing to want this might be a worthy first step. In the meantime, we’re left to reflect on the fact that even the world’s worst dad is a more definite and real than money.

Is Alexander Skarsgård’s entire brand based on the idea that anyone that handsome would necessarily be evil? Is his goal to formally de-couple the beautiful from the good in human affairs, once and for all?

The excursions seem to occur once per season, but the outdoor spaces are reliably converted to resemble indoor ones.

In their terrible post-coital conversation, Tom, who grew up relatively poor, reveals to Shiv that he does want money, and, he suspects, so does she. I don’t think he has her quite right. But at any rate, they actually laugh at the idea that someone would do something, would give up money in particular, for love!

Even Lucas Madsen’s feckless, fash-ish tech bro irony brims with life when placed next to the Roys. He understands that nihilism needs the temporary veneer of inroad to maintain a certain plausible deniability.

I so relate to the "hard to watch" sentiment. My wife doesn't watch, but asks me about it occasionally. Last night when I watched this episode she asked me how it was and my off-the-cuff response was, "It was good, but I'm excited for the season to be over."

I’m so relieved you made the Arrested Development connection because I observed the same thing!

I’ve been voraciously consuming any kind of analysis of each episode and am thrilled to read your thoughts, particularly relating to Aristotle.

As I watch these following episodes, I cannot get Logan’s words out of my head: “I love you, but you’re not serious people”. Logan alluded to his difficult upbringing, one where we can presume he was not taken seriously and we can see this this (successfully) becoming his life’s mission and ultimately, his primary accomplishment, arguably in sacrifice to everything else. The entire series the children seemed only interested in him taking them seriously as individuals which, frankly, seemed to bore Logan as he loathed their dependency or worse, used this to his advantage to manipulate them. Now that Logan is gone, their presumption that they should be taken seriously is an angle each of them desperately searches for to no avail because while Logan may have gave/pretended to/withheld love, no one else is interested or obliged to. With maybe the exception of Tom(?) you’re right that there is no love. We only get small whiffs of approval from others but it’s always for their own selfish gain. This episode in particular reeked of their separate attempts (and failures) at being taken seriously each taking on aspects of Logan but also taking on the role of Logan for each other. Is this strangely out of love? Would they recognise it as such? What is it that they really want? If Logan is gone, is it even attainable?