The Light in Which It Which It May Be Understood

Learning judgment from Jane Austen's Pride and Prejudice

The novel Jane Austen titled Pride and Prejudice was originally called First Impressions. “Pride” and “Prejudice” are two characteristics related to judgment which inform how we arrive at first impressions. Pride influences how one evaluates one’s own worth in relation to others; prejudice is how one sees the worth of others in relation to oneself. Depending on one’s perspective, pride and prejudice can be either vices or virtues, and seem to straddle the line between moral and intellectual characteristics. Improper pride or invincible prejudice make it impossible to move beyond our mistaken first impressions: having ourselves or others fundamentally wrong removes the incentive to keep inquiring. Proper pride and discerning prejudice, conversely, help us navigate a world in which people and things are constantly presenting themselves to us for judgment. The world appears to us as a series of first impressions. How can we allow them to impress, rather than fitting them into a mould we prepared long ago? At the same time, are we consigned to always starting from scratch? The question of how one develops good or improved judgment seems generically related to the question of how virtue can develop in the first place—it is the cousin of the “pugnacious proposition” from Plato’s Meno; namely, one cannot seek for what one knows, but neither can one seek for what one does not know. If we experience pride or prejudice as vices, can we ever learn to formulate good first impressions? Can we be habituated into good judgment, or must good judgment be taught as a form of knowledge?

Pride and Prejudice depicts many first impressions, often inviting us to make our own. A detached and seemingly objective narrator—critic D.A. Miller suggests that Austen’s characteristic style is writing “like a god”—sometimes metes out definitive assessments of people’s characters, but these usually arise after we have started to judge the character based on their prior speeches and actions. Austen plays with our perspective in order to encourage certain judgments: if she writes like a god, she is Athena—or Mentor—from the Odyssey, deceiving into the truth. In the opening chapter, we see the clever Mr. Bennet taunting the silly Mrs. Bennet about whether he will call upon Mr. Bingley, the “single man in possession of a good fortune,” newly ensconced at Netherfield Park. We are impressed with the sharp Mr. Bennet and his condescension toward his wife seems natural, deserved. When the narrator belatedly tells us he was “so odd a mixture of quick parts, sarcastic humour, reserve, and caprice,” we’re inclined to ignore the fact that this evaluation is lukewarm at best, having already enjoyed his wit. This is doubly so because Mrs. Bennet is in the next sentence described as “a woman of mean understanding, little information, and uncertain temper.” Our first impressions are difficult to dislodge.

But as Chapter II opens, we learn despite his somewhat cruel mockery of his wife and daughters, Mr. Bennet is among the first to visit Netherfield. It may be easy to dismiss the silly Mrs. Bennet, but her evaluation of Mr. Bingley’s significance is shared by her husband—a truth “universally acknowledged.” Mrs. Bennet does little to redeem herself, and is persistently unpleasant and prone to quick, shallow, and dramatic judgments. We see her interest in marrying off her daughters as desperate, approaching risible. The narrator does not share the details of the Bennet daughters’ precarious financial situation until Chapter VII of Volume I. We only then learn that Mrs. Bennet is so concerned about her daughters’ marital prospects because of the dire financial consequences of a failure to marry “well.” Longbourne estate is entailed to a distant male heir—Mr. Collins—and the options for the Bennet sisters (to say nothing of Mrs. Bennet) upon the death of Mr. Bennet are severely constrained.

Does this critical information change our evaluation of the Bennets? The narrator of Pride and Prejudice has shown us bad behaviour without informing us of the mitigating circumstances. This is a good estimation of how we might actually come to know a family like the Bennets: people do not provide the entire context of their lives when first we encounter them. If we are being totally fair, we should probably revise our estimate of Mrs. Bennet upwards, and, like Mr. Darcy eventually, come to think rather less of Mr. Bennet, who has failed to provide for his family’s future through prudent financial planning or education. The circumspect but carefully orchestrated plotting and narration of Pride and Prejudice constantly put Austen’s readers in the position of the characters in the novel; powerfully tempted to settle an opinion while in possession of partial information, of first impressions. People who love Jane Austen often fancy ourselves wry sophisticates like Elizabeth or Mr. Bennet. We rush to conclusions about Mrs. Bennet, whom we deride for constantly rushing to conclusions. The narrator, however, will suggest a more rational basis for Mrs. Bennet’s anxieties. Perhaps she’s not the only one who is being shown as silly.

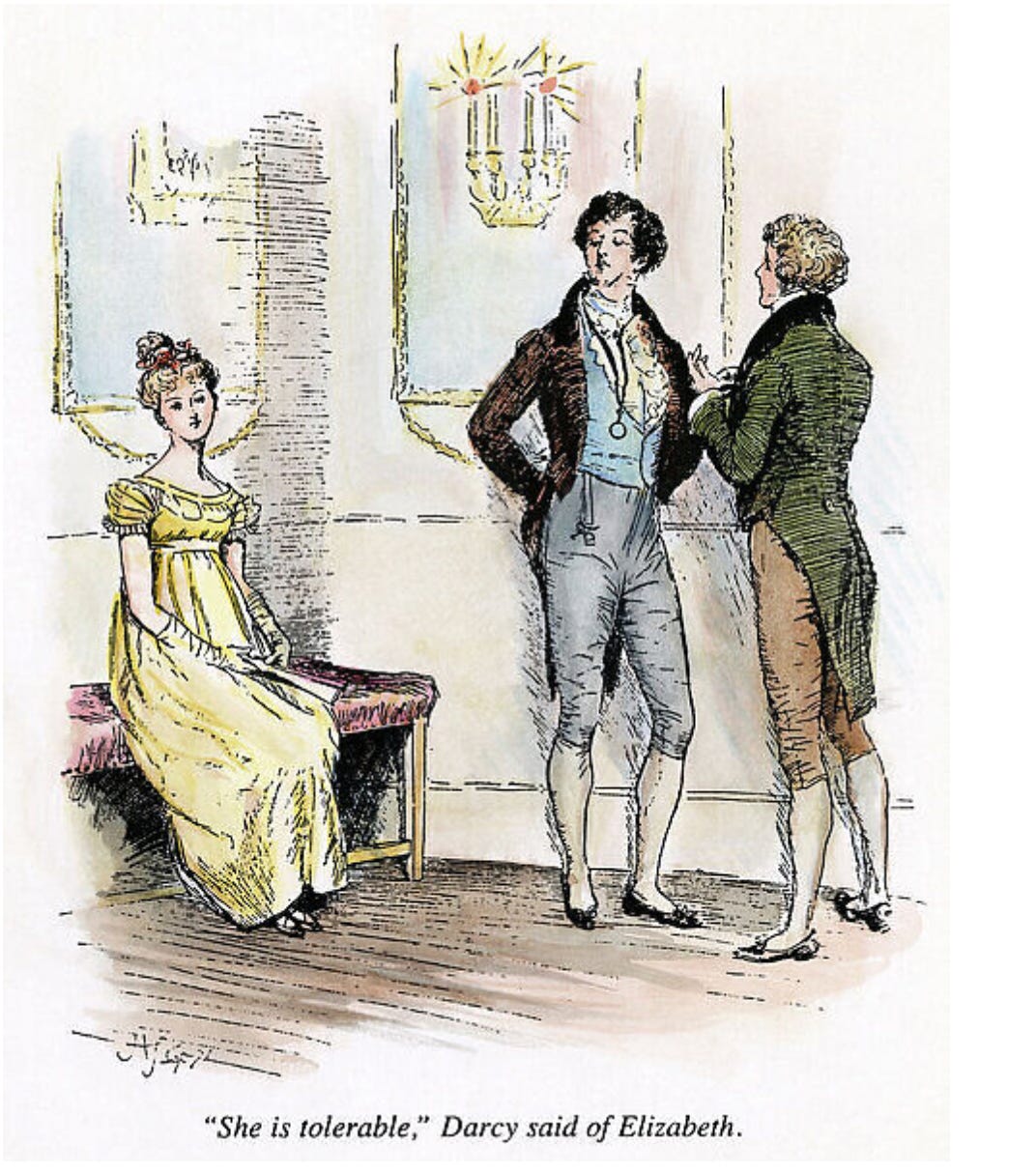

Of course everyone loves Elizabeth Bennet from their very first impression of her. It is Elizabeth whom Mr. Bennet favours among his daughters, and whom the narrator introduces as having a “lively, playful disposition, which delighted in any thing ridiculous.” If we are not inured to the significant charms of Jane Austen it is surely because we, too, delight in ridiculous things. Our inclination to like Elizabeth is encouraged by our sense that, in their first interaction, she is unjustly snubbed by the proud Mr. Darcy. How much better still that Elizabeth takes his insult in stride, turning the embarrassment into a story shared with “great spirit” among her friends.

Our sense of the witty and perspicacious Elizabeth Bennet is thus carefully established early in the book. We like Elizabeth so much that we risk thinking Pride and Prejudice more boring than it is: if our heroine starts out more or less wise and good, what is there left but for things to happen to her? We admire Elizabeth no less for her spiritedness, her willingness to assert herself, to speak on behalf of nature against convention. Elizabeth seems to be unmoored from the stifling conventional bonds of her world, and her sensibility flatters modern readers more still. How like us she is.

We are told comparatively little about Jane Bennet, having not received an objective evaluation of her from the godlike free indirect discourse. Curiously, we never get one. We see Jane exclusively through the eyes of others. When Jane and Elizabeth meet to discuss the Netherfield Ball, we learn that Miss Bennet was circumspect about her views, waiting until she was alone with her sister to share her thoughts. On Mr. Bingley: “He is just what a young man should be….sensible, good humoured, lively; and I never saw such happy manners!—so much ease with such perfect good breeding.” Jane’s evaluation is obvious and anodyne, the sort one might expect to have from one evening’s acquaintance. Elizabeth adds: “He is also handsome…which a young man ought likewise to be, if he possibly can. His character is thereby complete.” Jane only adds that she was flattered to be asked to dance a second time, noting, “I did not expect such a compliment.” Elizabeth’s wit once again sparkles as she replies: “Did you not? I did for you. But that is one of the great differences between us; compliments always take you by surprise, and me never.” Elizabeth understands everyone’s relative merit correctly, and so compliments only reflect the way things are. She does add that Jane was probably asked because she was “five times as pretty as every other woman in the room.” Mr. Bingley was not moved by his character, or Jane’s, but by his eyes. Elizabeth’s comments strip away nobility as a motivation for action. It would be understandable to conclude that Elizabeth is such good judge because she sees our base motives for what they are. Thank goodness the naive Jane is here set straight by her clever sister, who cuts through appearances to see things as they are.

There is a second, more telling, confrontation between the two sisters, in the first chapter of Volume II. When it looks as if Mr. Bingley has, under the baleful influence of his sisters, spurned Jane and quit Netherfield for good, Elizabeth is righteously indignant on her sister’s behalf; Mrs. Bennet, inconsolable. Jane laments her mother’s lack of self-control, the way her constant “repining” affects her own feelings. Jane is confident that if only everyone would stop talking about it, she could forget about Mr. Bingley in no time. Elizabeth is not so sure, giving her sister a condescending look of “incredulous solicitude.”

Jane’s position might be categorized as “philosophical” in the colloquial sense: she was mistaken that Mr. Bingley had feelings for her, and so the fact that he has moved on can inspire neither hope nor fear in her. Elizabeth’s reaction: “My dear Jane!…you are too good. Your sweetness and disinterestedness are really angelic…I feel as if I had never done you justice, or loved you as you deserve.” Elizabeth reinforces our sense that Jane is too good to be true. Miss Bennet is “sweet and angelic,” but not sufficiently “dissatisfied” with the world, with the “inconsistency of all human characters” as Elizabeth, who has been recently disappointed by Charlotte Lucas’ decision to marry Mr. Collins as much as Mr. Bingley’s apparent decision to leave Jane. But it is Jane who judges more as the action of Pride and Prejudice encourages us to do about the Bennets themselves, to consider the “difference of situation and temper” in Charlotte’s case. On the issue of Mr. Bingley, Jane counsels against being “so ready to fancy ourselves intentionally injured…It is very one nothing our vanity that deceives us.” Jane raises the titular vice of vanity, or pride, as a potential distortion of our ability to judge.

Jane is, moreover, aware that Elizabeth believes Caroline Bingley to be the cause of Mr. Bingley’s move to London. Jane articulates her reasons for thinking as she does, and they are impressively rational and consistent. Mr. Bingley’s sister must wish for his happiness. If he loved Jane, she would want them to be together, and could do little to actually stop them; it is, moreover, perfectly reasonable for her to prefer the rich and noble Miss Darcy, whom she has known longer. If Mr. Bingley loves her and is still somehow kept away, Elizabeth would make “every body acting unnaturally and wrong” and Jane “most unhappy.” Jane needs to assume people are rational, that they always pursue some good—including the ultimate good of happiness—in their choices. She concludes her speech to Elizabeth by saying: “Let me take it in the best light, in the light in which it may be understood.” Whatever the ultimate theoretical incompleteness of the assumption of rational teleology for human action, Jane posits that it is required to understand why people do the things they do. Given that this is the case, she practices what Aristotle might call a certain sungnomē, knowing-with, in her evaluations of others. This means using the “light” in which actions may be “understood;” that human beings are not random, but purposive creatures.

She is thus the only resident of Herfordshire who is right about Mr. Bingley, pleading “extenuating circumstances,” urging “the possibility of mistakes.” The action of Pride and Prejudice vindicates Jane. Our first impression of Elizabeth leads us to imagine a certain hard-nosed pessimism about human nature reveals people’s true motivations; but, given the dangers of, well, pride and prejudice, Austen hides an alternative in plain sight in the perspective of the older, “naive” Bennet sister, very aptly named “Jane.” Our first impression of Jane makes us loath to trust her, and it is easy to miss that Elizabeth’s difficulties could be solved were she more like her elder sister earlier in the novel. We can begin to learn to judge without pride or prejudice by positing, as does Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics, a book with an epigrammatic first line every bit as famous and questionable as Austen’s, that every action and activity is held to aim at some good. It’s no achievement to be hard-nosed or cynical: learning to judge does not mean always assuming the worst, because that’s too easy. Austen shows that, given the predominance of pride and the inevitability of prejudice, the best judges assume human action is telic; they assume, in other words, that judgment itself is a possibility. 1

I presented a draft of this essay at last year’s Association of Core Texts and Courses annual meeting at Notre Dame.