Permission Structures

How AI-skeptic Professors Can Still Help Students Write Papers

I spent the period between the end of the last academic year and the beginning of the new one (“summer”) fretting about the fate of liberal education in the age of AI. I did some tweeting about it, as one does, and some of those tweets struck a chord. My mother saw a screenshot of my “B or C student” tweet out of context on Facebook and first asked me if I was in fact “second sailing,” then proceeded to ask me: “And what do you get for writing such a viral tweet?” What indeed.

The biggest of these tweets happened in April of last year, as I was grading final papers, and expressed a sentiment that I guess I wasn’t alone in feeling:

To belatedly answer my mom’s question, one thing I eventually “got” from this tweet was credibility from my students on the AI issue. Is this something you should get from a tweet? Obviously not. But the students certainly come in thinking that social media metrics are significant, so I’m quite happy to use it as a rhetorical entree to the issue.

I think I am pretty good at AI detection.1 So far I have only found one borderline case out of a group of sixty first-year students in an elective class. I think this is a very good outcome. It’s so good that I have frequently found the students’ evident decision to choose to learn, to choose something difficult, beautifully moving.

In what follows, I’ll lay out what I did, and why. I hope you will find it helpful.

Background and Principles

I don’t have a nuanced position on AI in humanities education.2 Because I am a moderate, reasonable chap, this lack of nuance should give me pause; it doesn’t. I do not “believe in” liberal education. I know it’s real, and, through luck or Governance, I have seen it happen. I don’t have to believe in something that exists. Insofar as LLMs are used to avoid reading, thinking, and writing, their use is incompatible with liberal education. It is not more complicated than that.

I also find the idea of anything even vaguely punitive in the university classroom embarrassing at best, and against the very idea of education at worst. I am not going to become the AI police. I don’t want to do investigations and I don’t want to punish students. So part of my approach is informed by my conviction that education is a realm of freedom that should be as non-carceral as possible. I don’t care if that sounds “high-minded”—it’s no higher than education is or deserves. But I also think that students increasingly don’t know what our expectations are, and that it is a real disservice to fail to be explicit about those expectations. So I am up front, embarrassingly earnest probably, about the fact that I believe what we’re doing is very serious, and why I think that the use of LLMs is incompatible with that pursuit.

Finally, and I recognize that this is not a small thing, but my students are self-selecting. St. Thomas University, where I teach, offers only the BA and my students are the ones among that cohort who decided to do Great Books.

However, the relevant class here is a departure from our usual pedagogy. All other classes in our program are small, team-taught, seminar-based, and with the same cohort for an extended period of time. The students who usually take my classes are extremely familiar to me (and with me), write many papers, share their thoughts in class regularly, and care enough about their own education that they do not use LLMs.

This year I am teaching, for the first time, a “regular” large-ish (60 student) introductory class. We have added this class in order to give students a less intense or intimidating point of entry to our program than our usual first-year seminar. Since the students in this first-year class were a different case, a different approach was necessary.

My final principle is that I am willing to do a lot more work in order to give the students a chance to learn. As my colleague Jonathan Malesic put it in The Hedgehog Review: “I will sacrifice some length of my days to add depth to another person’s experience of the rest of theirs. Many did this for me. The work is slow. Its results often go unseen for years. But it is no gimmick.” Another viral tweet of mine suggested this as something like a Hippocratic Oath for humanities professors—perhaps we could call it the Socratic Oath. But it is the true, crazy thing I believe.3

My Theory of the Case

Why do students use LLMs to write their papers? My theory of the case is twofold: they have not been given the opportunity to think about why education is worthwhile or even what it truly is, and they experience significant anxiety about their work as students.4

To respond to this theory, I decided on three guiding ideas for planning my course:

Students need to have the chance to think about the significance of their own education in a serious way.

I needed to be very explicit about the purpose of everything I asked them to do, and about connecting it to this sense of purpose.

My students needed to feel sufficiently secure that they were free to take the intellectual risk I was asking of them.

What I Did

I raised standards, but lowered the stakes.

One advantage about teaching in a Great Books Program is that it’s not that hard to find an agreement between form and content on thinking through the meaning of education. Without an obvious vocational goal, we have to get serious about what we’re doing. To wit, I had the students read hard books: Plato’s Apology of Socrates, Aristophanes’ Clouds, the entirety of Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics, Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice, and Dante’s Inferno. Both Austen and Dante were presented as different interpretations of the significance of the Ethics. Of course these books are about an entire cosmos of human affairs, but I focused our discussions around what each had to say about the nature and purpose of education. I let them know that what they were doing were hard, I gave pep talks, was relentlessly upbeat and positive, and I told them that what they were doing was counter-cultural in a precise sense: in a world where huge corporations want their attention spans reduced to 15-seconds, they are building an inalienable capacity that will give them an advantage in any pursuit, but also might make them happier human beings.5

I also made it very, very easy to pass the course. In order to get a D, all students needed to do was come to class and complete their five in-class writing exercises. The writing exercises were all related to the theme of the course and, to a limited extent, verified their reading.

As I frequently reminded the students, if they did all their writing assignments and missed no more than three classes, they would pass the course regardless of whatever else they did. If they wanted to do better than that, they would have to write a paper themselves (and also do well on the exam).

They should therefore feel free to not worry so much about their work for my course (aside from the very large amount of reading I required). If they didn’t meet my expectations on the Writing Exercises, I did not hesitate to invite them to try again. They almost all always did so.

In sum, I helped students understand that their work should matter to them. I helped them read books that made maximalist cases for the significance of education to their lives. I empowered them to do good work without the implicit threat-structure of traditional grading. The results, I think, speak for themselves.

How I Used In-class Writing

Each writing exercise was designed to reinforce explicit instruction on different paper-writing skills.6 Here are the skills I asked them to practice:

(1) Using textual evidence and citing the text

(2) Analyzing an argument

(3) Close-reading a passage

(4) Comparing two texts

(5) Synthesizing ideas and arguments across several texts.

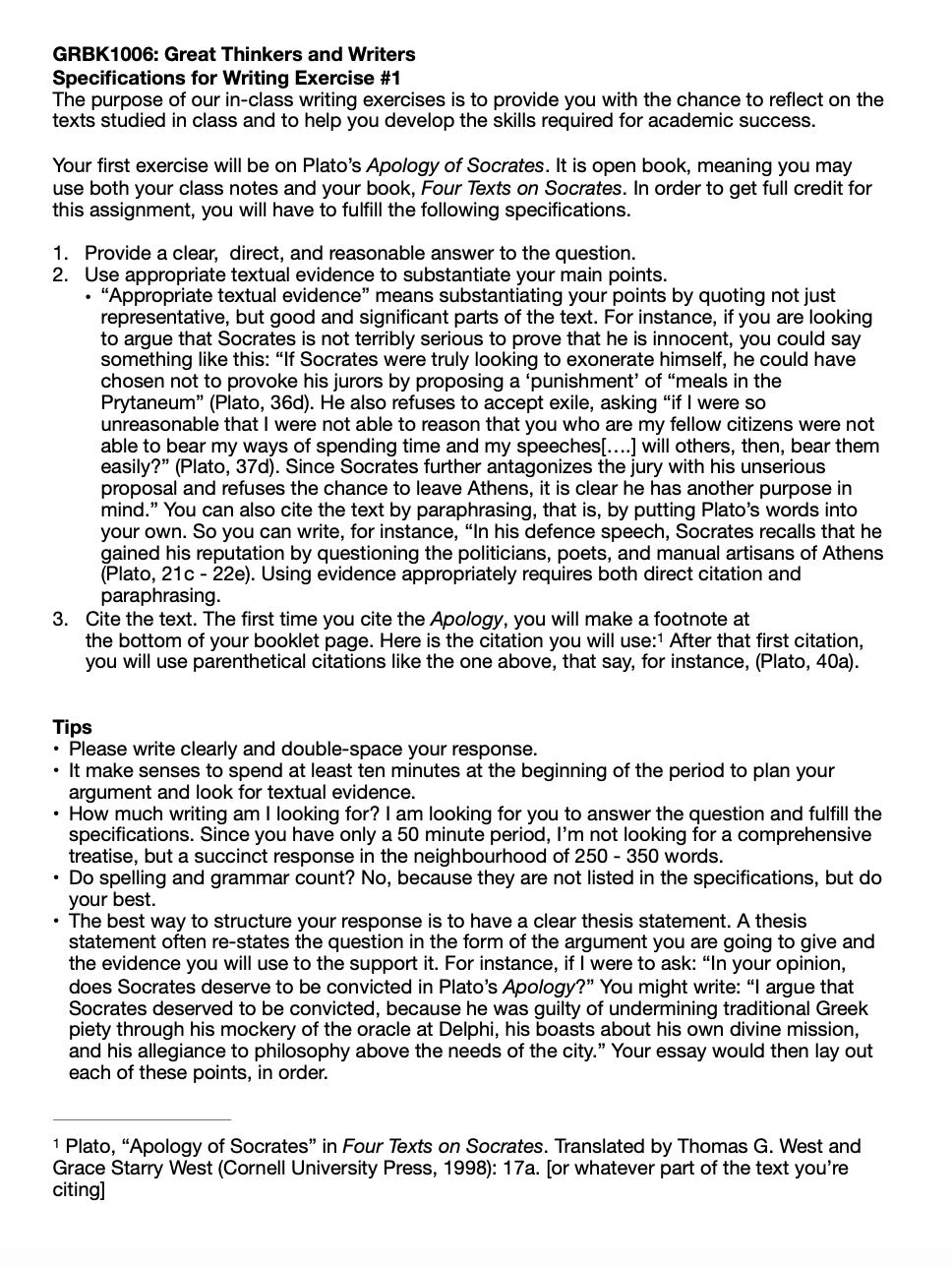

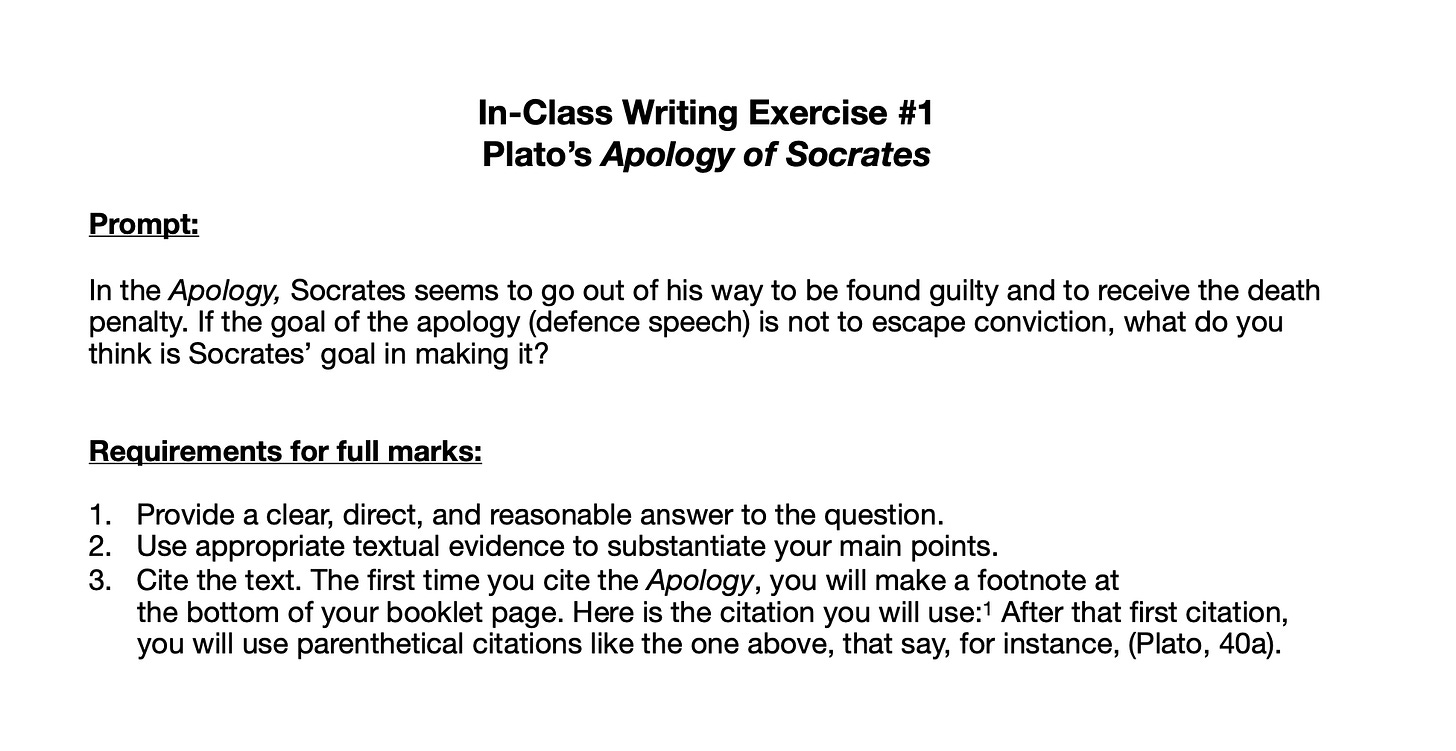

Each assignment involved writing something linking their reading to the class theme. These assignments were done in “blue books,” and I graded them using a modified version of “Specifications Grading.” I distributed the specifications in advance, and gave the students the opportunity to rewrite the exercises if they failed to achieve the specifications. It was logistically complex, but it was ultimately worth it. Here is an example of the specifications I provided, which I discussed with the students in advance:

Then, in class, I just gave them the question that was already on the specifications page. I did not do this after the first one, of course. You might complain that this is too easy, and, to an extent, I agree with you. But this is a year-long class, and I am playing the long-game: I want students who are on board, and who want to learn, and who understand why they want to learn. I’m not looking to punish or trick them. The stronger students took the prompt far deeper and made far more interesting connections, and the weaker students gave fine answers and passed the assignment.

By the time I assigned their term paper, in November, the students had already practiced all the skills they would need. In the document I made to guide them in paper writing, I was explicit in reminding them that they had all already successfully shown that they had these skills. The students understood that, having learned to properly cite the text and use textual evidence, that they needed to continue to practice these skills in their subsequent writing exercises, and that the purpose of this was to eventually deploy these skills in writing a paper.

I Met With Every Single Student

The most time-intensive thing I did was to meet with every student to discuss their paper ideas. They came to my office, sometimes in groups of two or three, and I helped them turn their ideas into a thesis statement. Some students came with complete drafts, which I’d read, and, for some of them, they clearly came up with their ideas on the spot. I was able to push some students to intensify their analyses and think through their arguments more deeply. I headed some very bad ideas off at the pass.

The effect, which I told them in class, is that I already know what they were thinking about. I helped them refine their ideas, and in some cases I challenged them to ensure that they were finding better evidence from the texts to support their arguments. In a general sense, I also got to chat with the less-chatty students and get to know them, personalizing the teacher-student relationship, and making it clear that we were not involved in a transaction.

I fell behind on absolutely everything during this two-week period.

I will be doing it again next term.

We Spent an Entire Day Studying an Excellent First-Year Paper

In addition to all this explicit instruction, I also gave the students a clear model of what I was looking for, and we read the paper, written by another first-year St. Thomas Great Books student, together in class. I didn’t tell them much at all, instead we’d finish a paragraph and I’d say: “How did this student use evidence?” “What do you make of this sentence?” or “Why did I think this paper was so good—tell me the top three reasons.” The students were extremely enthusiastic. The paper was also about Aristotle’s Ethics, and so they had the chance to think more about the book, which they had just finished studying.

Conclusion

The effect of all this, was that the students were not only intrinsically motivated to do good work, but I created an incentive structure in which there was really no point in not doing it. It was a lot of work for me. The work was worth it, in part, because I have these students all year, and so part of what I have done is a down-payment for better work in semester 2 as well. But the success of my method tells me two things:

(1) The time for college professors to haughtily suppose the value of what we do is self-evident is well and truly over. You need to be explicit. You need to show them something beautiful, and support them in its pursuit. I suppose I am grudgingly grateful for the AI humanities apocalypse—apocalypse of course meaning un-hiding or revelation. The days of terrible pedagogy and bad teaching have to end if you really care. The students are hungry for the real thing, but you have to help them want to want it.

(2) The noble things are difficult (kalepa ta kala). This has always been true, and the challenge now is perhaps different than it was even in the context of my career. But if you think that liberal arts education is worth doing, you have to be humble enough to accept the hand you’re dealt and work on a strategy.

Maybe I am a fool and can’t tell or don’t know anything. My theory is that LLM use has to do with anxiety. If it is willful vice and the desire to deceive or cheat— a desire as old as time—there’s nothing I could do about that under any circumstances. So I’m assuming, perhaps, that this is so in some cases, but I don’t know what’s truly going on in people’s minds or hearts, thank God, so I have to judge by the evidence I have. That evidence is a series of delightfully eclectic and winsomely imperfect works of student writing.

You’re welcome to peruse the Prefaces back-catalogue on the issue if you want some arguments.

I understand that I am an outlier and that I am fortunate to be tenured and relatively well-resourced in a public, Canadian SLAC.

This anxiety has many sources. Economic, cultural, existential. But a lot of anxiety is also caused by students not understanding expectations and nobody telling them what they actually want.

We also spent entire classes on practicing close-reading, I gave study questions to guide their reading, and I leaned on my excellent upper-year students to offer conversation and tutoring.

My approach here was inspired by McGill political theorist, Jacob Levy: https://www.chronicle.com/newsletter/teaching/2025-05-22

I spend a lot of my time doing talks and seminars on how to address the challenges of LLMs, particularly in the context of getting students to read/think/write, and this is an excellent model I'll be pointing people towards in the future.

I've always found that the personal conferencing is a major key to success in all things. Even 15 minutes where it's clear to a student that someone else is taking their ideas seriously is tremendously motivating, and that signal you send that you're paying "attention" is invaluable.

I think a lot of this would help in motivating a high school classroom too -- obviously high schoolers can tend more apathetic and educationally-traumatized than an undergrad enrolled in a great books course.

Is there anything specific you'd consider doing differently with high school kids?