It's not just a calculator

The fact that we had a global emergency that became a professor emergency only four years ago should not obscure the reality that genuine pedagogical disasters are rare. In a way, teachers are always having to respond to everything that happens in the world, because we are in the world and more importantly, so are our students. This is part of why you have to remain just a little bit young (metaphysically) to be a teacher of any sort. If you lose patience for the whims, eccentricities, and annoyingness of the young, you will no longer be able to teach. And so there is a sort of constituent weirdness, a cultivated, strategic immaturity and affection for immaturity that even the most venerable teachers never fully lose.

Most good teachers therefore develop a salutary openness. Conservatives on campus are more open or expansive than conservatives elsewhere (the professors, let’s not forget, are “the enemy”) because of the sort of liberalism of the campus. This also makes campus politics wild and whacky in the millions of ways we’re confronted with all the time. The campus is a padded world: the sharpest corners are ideally covered up, so that while students sometimes get hurt by their new freedom, they will ideally not get hurt too badly. It’s a place where mostly young people are trying out being someone new all the time. Professors have therefore seen it all before, and are generally ok with undergraduate eccentricity, because almost everyone knows that we’re in the transformation business. We know that education is not simply a transfer of knowledge from one mind to another, or picking up certain skills: it’s about becoming a person who thinks, speaks, and is otherwise than the person who first shows up. We learn that we can’t be open to this good thing happening without being open to all sorts of other less good things happening, too.

This openness means that professors love novelty. Often enough it is to our own detriment, but professoriate have seen enough “craziness” become accepted wisdom to be generally enamoured with new things. As a profession we are open in a salutary way, but it is also something like a matter of pride for our guild to give everything a fair shake. It seems unsophisticated or reactionary to simply ever say “no.”

This has been the general professional attitude about ChatGPT—LLMs—more generally. We want to take a harm reduction approach. We’re cool, and so we will teach you how to use it. “We’d just rather if they’re going to do it, they will do it under our supervision, where it’s safe”—the chorus of cool parents everywhere. I have done this, plugging an essay prompt into ChatGPT with my students and then spending time in class showing why it does a bad job writing a paper—hallucinating quotations is only the start, it turns out. It is actually useful to have an example of a formally well-done but pat and uninsightful paper. It also signals that I’m aware of how it works, and so on, but at the end of the day, anyone can cheat. You have to help students see why it should matter to them that they become educated. Under the conditions of modern higher education, some people do not want that, and while I view this as a personal insult, it is ultimately, I suppose, just a structural reality.

But some professors believe that too negative a stance on AI in the classroom will one day look foolish. This is something like the summum malum for a certain type of political liberal, who then attempts to lives preemptively in the shadow of history—as if history had a direction, or were somehow under our control. The inevitable refrain is something like this: “I remember when professors used to tell us we weren’t allowed to use calculators!”

Let’s think about this comparison for a moment. What does a calculator do? It calculates, perhaps it graphs. It performs arithmetical operations. And so when you use a calculator, it may be the case that your mental math skills slips a bit. Most people are fine with the trade.

How would the comparison with LLMs work? Well, it would be something like this: an LLM is just another tool, like a calculator. In the past, we were anxious about the effects of this technology in a way that now seems quaint. Every time a new technology is introduced people panic—a “moral panic,” they like to say, because, you know, morality is not cool, and so a moral panic is not just unjustified, it is uncool. There is also a practicality version of this argument: don’t you want your students to know how to use ChatGPT? Everyone uses it in their jobs all the time, after all. And there is, finally, a broader, Donna Haraway direction, which would be something like: there is no such thing as un-mediated “knowledge production” in the first place—we are always already thinking with and through machines. For this way of thinking an LLM is no different from a calculator, which is no different, from writing—from language itself, which are all equivocally technological. QED.

These different lines of defence, I fear, are really motivated reasoning working backwards from fear of looking foolish in the future. It betrays a lack of confidence in what we as educators are trying to do. It suggests this openness and thoughtfulness, of worldliness and pragmatism. It’s just, after all, a calculator.

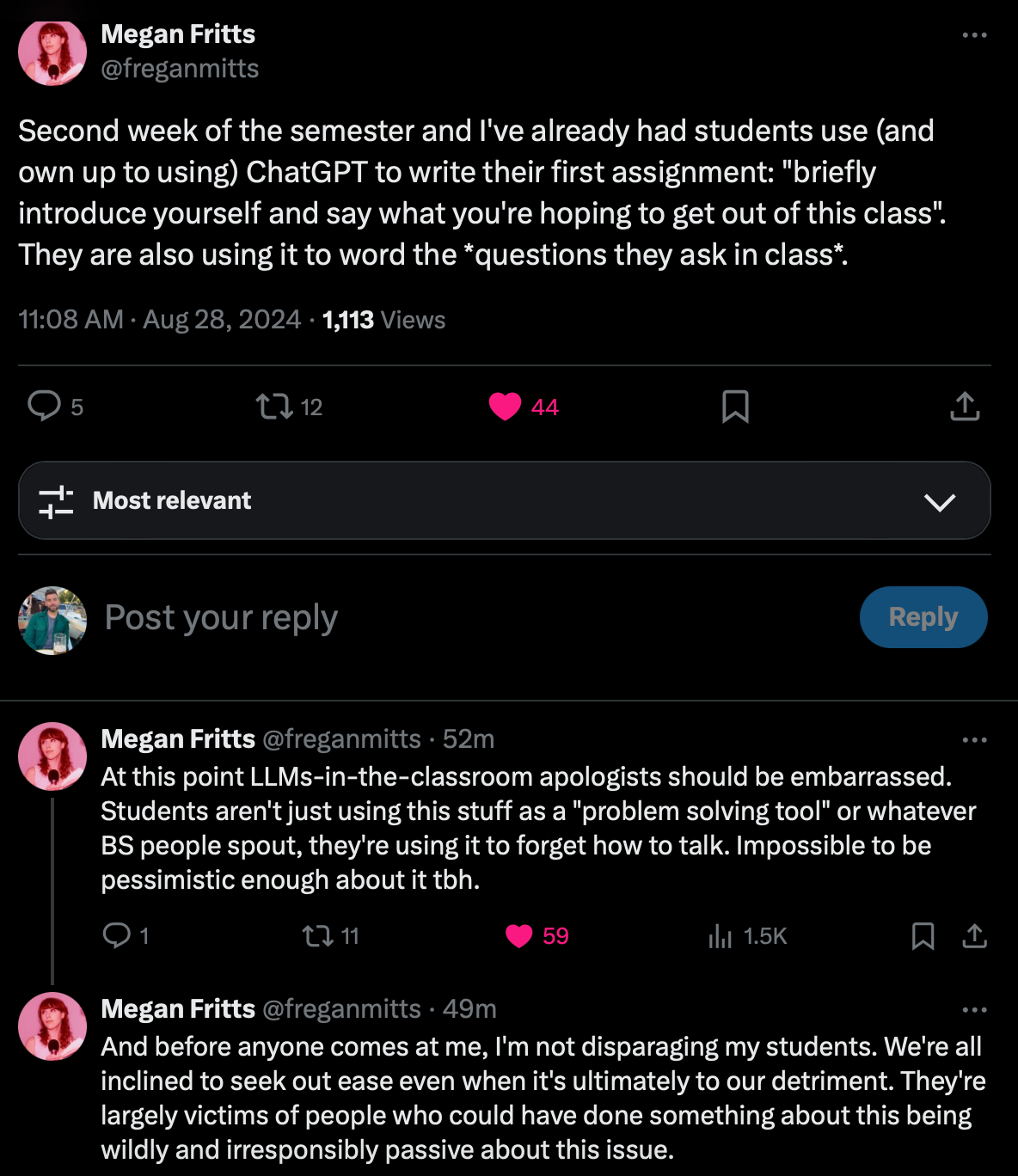

My reaction to AI when it first became an issue in higher education was that I was not really all that worried about it. That has, for the most part, been a reasonable response in my context. But we are now reaching an inflection point where it is necessary to go on the offensive a bit. Take this thread from my twitter mutual Megan Fritts, a philosophy professor:

I won’t bother spending too much time collecting additional anecdotal data, but I take Fritts’ experience to be an extreme version of something I hear about all the time. It is simply the case that we are doing a grave disservice to our students if we continue to take any version of the “it’s just a calculator” approach to LLMs.

So, naturally, I agree with Fritts that “LLMs-in-the-classroom apologists should be embarrassed.” They should be embarrassed because a calculator, very fundamentally, does calculations, it does not threaten the human capacity for speech. Perhaps I am being an “essentialist” about speech, but I am willing to hang my hat on this particular essentialism: human beings are the animal with rational speech. Speaking is our peculiar way of thinking together. When it comes to LLMs, we might therefore fairly ask: can we think and speak about the things we do? I reckon we can do this with a calculator in a way that we cannot with an LLM. What is more, if students now use LLMs to formulate questions in class, if it replaces the capacity for speech,1 then it is quite precisely not a tool, because it has ceased to be instrumental.

Even the most instrumentalist view of education still assumes human subjectivity that has ends for which that education is a means. There is still an I there that wants a job, and so wants to know how to code, to be a nurse, to analyze a budget. Behind the instrumentalist view the question of purpose sort of remains, often left unanswered or answered only implicitly, but at the very least we could at that point wrap those questions in a certain noumenal respectability—these sorts of purposes exist, but they are outside our capacity for scientific knowledge.2 I’d rather live in a world where the most important questions are at least given the respect implied by mysteriousness.

But if now the tool itself supplants speech, then we no longer enjoy anything like a free relationship with it: we are serving it. And with LLMs, that is increasingly what is going on.3 Hannah Arendt’s (please imagine I am now speaking louder over the booing and jeers) HANNAH ARENDT’s intemperate, but essential, prologue to The Human Condition addresses just this concern:

“The trouble [in the natural sciences] concerns the fact that the ‘truths’ of the modern scientific world view, though they can be demonstrated in mathematical formulas and proved technologically, will no longer lend themselves to norma expression in speech and thought [….] But it c Ould be that we, who are earth-bound creatures and have begun to act as though we were dwellers of the universe, will forever be unable to understand, that is, to think and speak about the things which nevertheless we are able to do. In this case, it would be as though our brain, which constitutes the physical, material condition of our thoughts, were unable to follow what we do, so that from now on we would indeed need artificial machines to do our thinking and speaking. If it should turn out to be true that knowledge (in the modern sense of know-how) and thought have parted company for good, then we would indeed become the helpless slaves, not so much of machines as of our know-how, thoughtless creatures at the mercy of every gadget which is technically possible, no matter how murderous it is.”

Arendt’s concern is that technical knowledge and thought might no longer stand in essential relation to one another. It seems quite clear that LLMs are a technology designed to accomplish just this feat: a technology that produces what looks like knowledge divorced from thought. That it would with truly incredible speed lead students to jettison speech, follows fairly precisely from Arendt’s analysis. A long time ago, we have wanted to do away we thought’s relationship to knowledge—now we are finally sophisticated enough to bring this about.

And so, what we do is no longer subject to thinking.4 A calculator allows me to do calculation instantly in ways that I would not be able to do without it, but I am still able to communicate these calculations with others, in writing and speech. LLMs supplant the inwardness that goes in to the production of speech. An utterance produced by an LLM comes from everywhere and nowhere, it takes the “who” required for education out of the picture. It is to writing what Arendt will later suggest bureaucracy is to government.

So for educators it is time to be less open about this technology. If we believe in liberal education as a liberatory project—however you understand what that means—we cannot do away with students. We need students to understand that we are not simply imparting knowledge to them, nor are we training them in skills. Education, especially liberal education, is a how more than a what. A person who has been liberally educated is free in ways that others are not. A person who has spent time reading, thinking, writing, and speaking about matters of intense human concern is not the same as a person who has not. A person who has outsourced that work to an LLM has not done these things. Liberal education is about liberation, and serving a machine is not liberation.

On some level we should be grateful that the threats to education, and the stakes for understanding what we’re doing when we try to educate people, have been made so clear. It might be difficult to find that gratitude, but at the very least let’s agree that it’s not just a calculator.

AND it replaces the capacity for speech at precisely the moment where you should be learning to speak more fluently.

My colleague Rachel O’Keefe refers to the subject matter of the Kantian noumenal realm as “the good stuff” with our students, which I find impossibly charming, fun, and true.

It is also very shocking how many people confuse LLMs with search engines, which, again, shows the aura of thoughtlessness surrounding its use.

How this might relate to the various political aspirations of the boosters of this technology is pretty straightforward.

well done, Matt!

Gee, Matt this is great.

It gets at something I have been thinking about, but points to the heart of the issue more directly than I had been able to articulate.