The Ne'erdowell

Three poems I have made about myself

Yesterday was Wallace Stevens’ birthday. I have a poem by Stevens—Not Ideas About the Thing But the Thing Itself—on my office door as a sort of reminder of the personal hazards of my professional work. This poem features a lot things I like: choirs, winters, thinking, annoyingly high-toned earnestness. We’re about a month into the term and I find myself feeling a bit submerged in a problem I’m learning to think of as Too Much Significance. Most of my life’s main tasks—being a dad, a friend, a husband, a teacher, and reading, writing, thinking, singing(!)—are a little oversaturated with the expectation of meaning. Everything is the most important thing. It seems symptomatic of our world that some of us have no chance to think, and others have to attend to the meaning of life on an almost industrial scale. Obviously it’s good, but it’s also a little much. And this expectation, always being on the cusp of the substantial, feels delirious when I am not doing those things, which is frankly more of the time, when I’m driving kids, cooking, cleaning, devising a plan to expel the raccoon from my shed before winter, writing emails, going to meetings, picking up a prescription to deal with my sinus infection, and so on.

Anyway, this morning in Fredericton was the first intimation of winter. The warmth of the river met the cold air and made the entire valley foggy. We still haven’t had our first frost—an unthinkable statement about this place in October as little as a decade ago. But winter, and Wallace Stevens, have me thinking about the need for a winter mind as, perhaps, the solution to my strange problem.

It’s interesting that three of the brainiest American poets—Emily Dickinson, Wallace Stevens, and William Bronk—all wrote extensively and provocatively about winter. The latter two, I think, picking up pretty consciously from the first. Dickinson’s most memorable winter poem, which I wrote about a few years ago, provides this uncanny reproduction of how it feels to step out into the cold. Its speaker straightforwardly attests, “Winter is good—His Hoar Delights,” before adding a line break that feels like catching your breath in the chill air: “Italic flavor yield/ To intellects inebriate/ With Summer.” Dickinson’s confidence in winter’s goodness—“his hoar delights,” oddly—catches us off guard. But to extract “Italic flavor” from winter’s “hoar delights” is not to reduce it to summer—there is snow at the top of the Italian Alps, too. Dickinson does not compare summer to winter. She tracks the metaphorical—but also, I think, literal—ways that our thinking is shaped by our experience of the cold.

The poem makes us wonder whether our shock at this testament to winter’s goodness might not come from our mind’s fixation on summer. The summer-drunk mind misses out on winter’s particular charms, pursuing the “quarry” of the world as undifferentiated, “generic.” The summer mind therefore expects of the world a certain homogeneity, tractability: Summer gets out of the way, leading us to assume a world we can easily know, and perhaps control. I wonder if the long academic summer is not part of my problem. It is unnatural to go from such leisure to such assiduity.

Is my expectation of significance a metaphysical version of the desire for mastery? As I am sitting in my very cold office—by long tradition St. Thomas does not turn the heat on until Canadian Thanksgiving—I can’t help but think that even if winter is less accommodating, it is no less good. We flatten the interesting texture of reality when we think of a world only conforming itself to our comfort.

Dickinson sees winter as “hearty—as a Rose.” The line again catches us off guard, like an early storm, because a rose is the very image of delicacy. Though the sorts of wild roses grown in New England and Atlantic Canada are also surprisingly hearty, blooming two or three times per season. The rose hedge in my backyard has started blooming in October and November in recent years. So winter has a paradoxical delicacy. It seems, and is, so unwelcoming, but it is also overlooked, poorly understood—and now, maybe, under threat. We are capable of doing damage to the idea of winter, by assuming it will be just like summer. Nobody looks forward to winter, Dickinson writes. It is “Invited with Asperity,” but refreshing, “welcome,” when it comes (and indeed when it goes). Dickinson shows us the view from which winter is good on its own terms. It is more open to a world ungovernable and strange—not unknowable, but indifferent to our desires. So her poem plays with our expectations and upends them, mimicking the odd motions of the winter mind it cultivates.

Wallace Stevens’ most famous poem, “The Snow Man,” owes much to Dickinson, I think. The poem remarks how “One must have a mind of winter” to regard “the frost and the boughs/ of the pine-trees crusted with snow” or the “distant glimmer of the January sun” and avoid “any misery in the sound of the wind.” Being able to behold winter without projecting my own feelings as an interested party requires unusual mental discipline. Maybe I’ve spent too much time with Kierkegaard and am losing the world to my own quest for real inwardness. The inwardness should let me see the thing itself, I think. But “The Snow Man” challenges us to remove ourselves from our observations, but it also locates a particular problem in doing so when it comes to winter. At the same time, the beauty of Stevens’ descriptions of the winter landscape—“junipers shagged with ice,” “spruces rough in the distant glitter”—is hard to register as beauty when we are reminded of the chill wind “blowing in the same bare place.” The winter mind tries in earnest to get out of the way, and let the snow be the snow. Even if I have to be earnestly invested in my own life, can’t I make this attempt at gelassenheit? Stevens concludes “The Snow Man” by suggestion that winter teaches us the necessary limits of our own thinking, which is a prelude to genuine beholding: “And nothing himself behold/ Nothing that is not there and the nothing that is.”

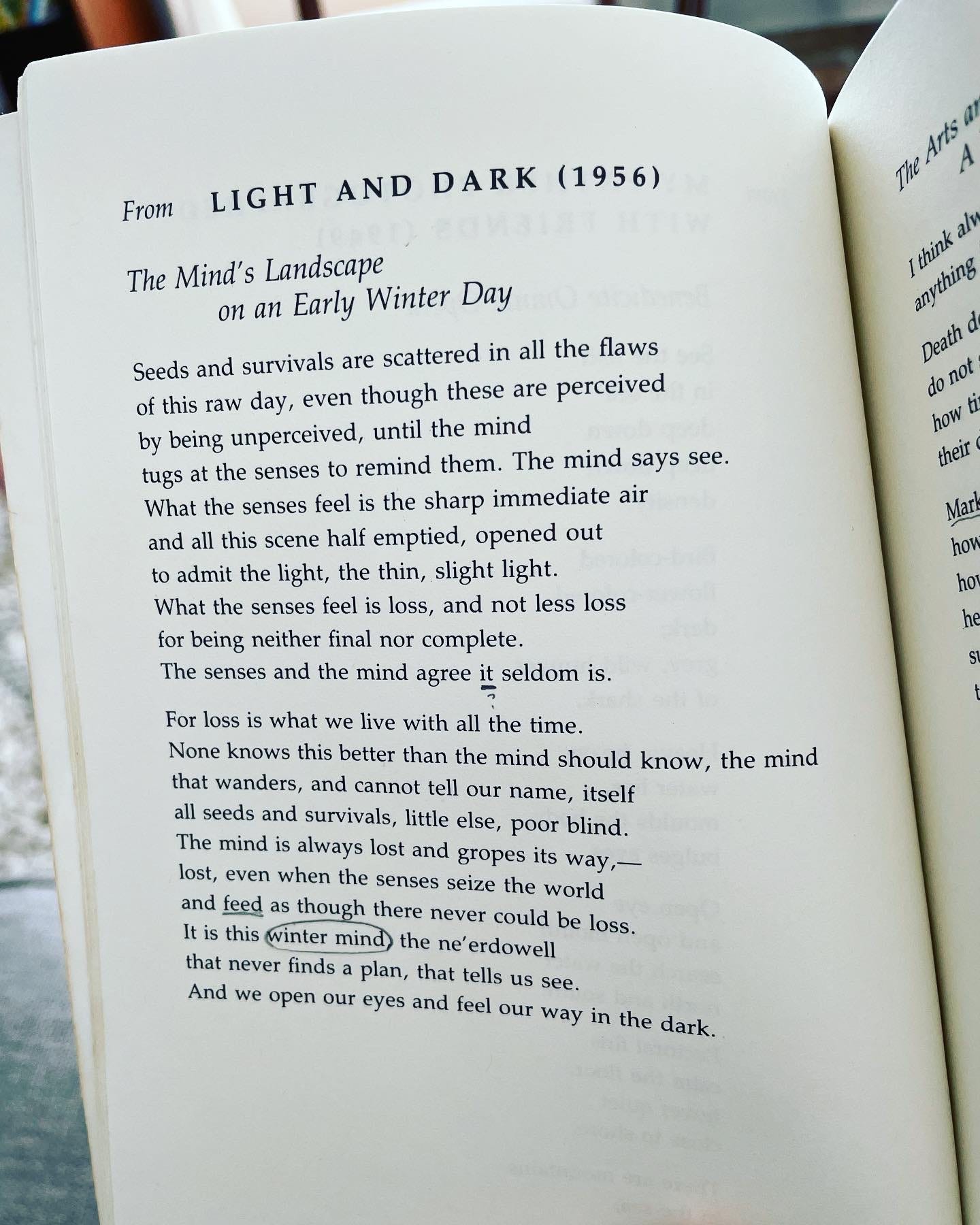

William Bronk, in “The Mind’s Landscape on an Early Winter’s Day,” pays homage to Stevenson and Dickinson’s winter poetry, but uses winter as an ingress for doubting we can know anything at all. Bronk notes winter’s “seeds and survivals” seen in its “thin, slight light” show us loss “For loss is what we live with all the time.” Sort of sitting here in expectation of the next big revelation feels like a refusal to live with loss. The mind is always lost, Bronk admits, the “winter mind, the ne’erdowell” can never find a way through. The Greek word for being “at a loss”—aporia—means being unable to find a door. The honesty of admitting it when you’re lost is not the end of our ability to know, but the condition of beginning to see things more clearly.

Perhaps Bronk's icy skepticism is a useful corrective to Dickinson’s “intellects inebriate,” but it might also speak to a longing for more “summery" certainty. Bronk feels betrayed by the winter mind because it still longs to know too much. I wonder if the mind is not as alone in the world as it seems. Bronk, or his poetic speaker, resents the uncontrollability of the “raw” winter landscape he surveys. Dickinson might, in her slant way, reply that the winter mind can know that winter is good, that it is more than a metaphor or a projection. Winter offers a chance to think differently, to know better by recognizing the ways our interest in control shapes how we see things. Acknowledging such limits is the prelude to genuine beholding.

Poems, it occurs to me, are a lot like winter. A poem takes its time, and forces us to take ours. A poem resists summary and upends expectations. A poem frustrates our efforts to grasp its meaning. Maybe my problem can be put this way: not enough poetry. I’m a prosaic person trying to force the prose into the poetic. Poetry is, after all, somewhat inhospitable to the mind’s search for understanding or certainty. It makes familiar language strange. So I need to think through, or learn to accept, this connection between the winter mind and poetry.

Winter minds incline toward poetry as both winter and poetry involve appreciation for the ungovernable. I’m approaching these poetic tasks of working with the ungovernable world, the slow work of thinking, of teaching, parenting, loving with the tools of prose. One of my colleagues recently told a bunch of students that I was “born wearing a suit”—an interesting thing to say about someone who does not wear suits. But I understand his meaning, and maybe there is a real problem here. My own sense of humour or irony does not fully extend to myself. I am too serious and need the winter mind, “the ne’erdowell/ that never finds a plan” but “tells us to see.”

So refreshing on this 90 degree day