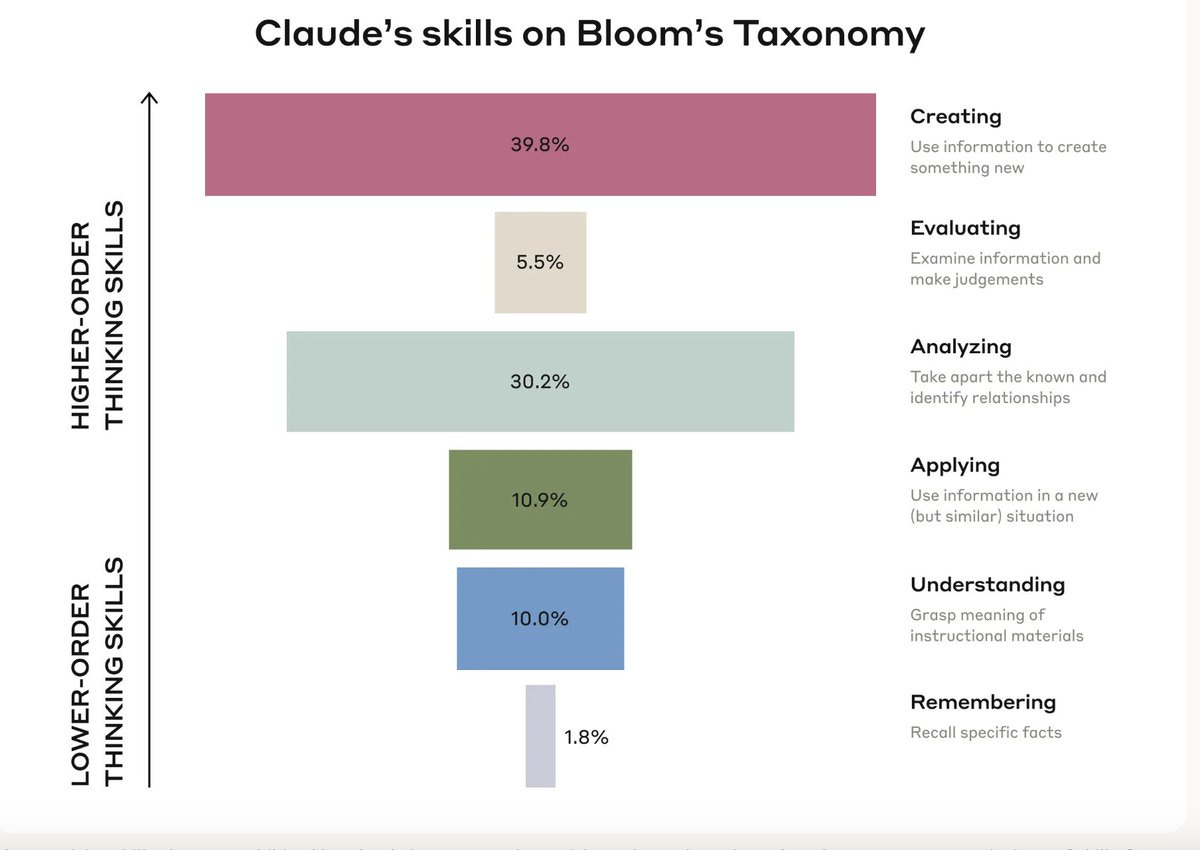

Anthropic has released an interesting and detailed analysis of how students use generative AI in higher education. For once, the most interesting tale is told by a chart.

To what end do students deploy AI tools? Put very simply: to cheat (“creating”), to avoid thinking (“analyzing”), and, these to taken together, to deprive themselves of what even so dreary a heuristic as Bloom’s taxonomy understands to be the higher life of a human being. In short, AI tools, heralded as the dawn of a great new area of human freedom, do not liberate us from drudgery; they liberate us from true leisure. Instead of replacing the things we would rather not do, AI tools help our young people evade the hard work of developing the faculties from which we derive the most pleasure, the things which make us distinctively human. (I presume the difference between my summary and what an LLM would give you is sufficiently clear).

The report’s authors have a series of questions evincing such naivety they may as well be rhetorical:

As students delegate higher-order cognitive tasks to AI systems, fundamental questions arise: How do we ensure students still develop foundational cognitive and meta-cognitive skills? How do we redefine assessment and cheating policies in an AI-enabled world? What does meaningful learning look like if AI systems can near-instantly generate polished essays, or rapidly solve complex problems that would take a person many hours of work? As model capabilities grow and AI becomes more integrated into our lives, will everything from homework design to assessment methods fundamentally shift?

The answers to the questions are as follows:

(1) We cannot as things stand. The development of such skills will only occur if students refuse to integrate AI tools into their own educations.

(2) “Redefinition” must here mean “do away with.”

(3) Meaningful learning will increasingly look like not using AI in education at all.

(4) Yes, but it will shift back in the direction of genuine education delivered person-to-person. Sadly, this will become the reserve of the rich and the privileged.

Understandably, the people whose livelihoods depend upon AI will not tell the truth about education; after all, they are not expert in that field. I am a moderate person by disposition and training, but I think it should be clear, by the self-reported data of AI companies, that what we are learning is that there is no alternative to actual liberal education.

For years now, we have tried to defend liberal education on the basis of “skills development.” This was already a concession that gave away the game: if an AI tool can have all of the “skills” I need, then I need very little by way of actual education, except training in how to use those skills. So I hope that we now understand the futility of the “skills” argument . The good news? The point of liberal education is not to develop skills. If you want to learn how to solve problems, play video games, or work in the service industry. “Skills” are cheap. Education demands that we know something, where knowing is “understanding.” Understanding means not only being in touch with a body of facts or concepts, but having them as a part of oneself—having an account of things that contextualizes knowledge and renders them meaningful—being able, by way of dialectic, to relate universals to particulars.

Learning how to think in a way that facilitates such understanding can only be done by watching others do it. The only good way to do this is to read books, where the best of us have been showing how to think aloud for millennia—and to have your thoughts challenged by others through conversation. There are no shortcuts and there are no alternatives. Insofar as other methods of instruction bring about these ends, it is because they incorporate the activities mentioned above. Education is not a product; it does not scale. It is a human relationship.

The great promise of technoscience, from Francis Bacon and Rene Descartes onward, has been the relief of humanity’s estate, an end of drudgery. The deep irony of both Bacon and Descartes is that they imagined—and helped effect—worlds in which we could not have another Bacon or another Descartes. I think that we are now on the verge of a remarkably similar problem: the ingenuity and insight required to develop these models will be destroyed by the models themselves. Liberation from drudgery becomes, at last, liberation from leisure, and thus liberation from liberation. I trust you’re all well-educated enough to figure out what that means.